This year I was lucky enough to receive the Wildland Fire Digital Story Telling Grant through the American Wildfire Experience. My vision with this grant was to bring to light the changing conditions Wildfire Fighters are experiencing and the ever-mounting challenges we face. By documenting what we call “the new normal” through the eyes of a Wildfire Fighter I hope to bring people face to face with the affects of climate change and show how it’s manifesting itself in the world around us. I hope by contributing to the story of Wildfire we can start connecting some crucial pieces to the puzzle of how to live alongside these natural phenomenas.

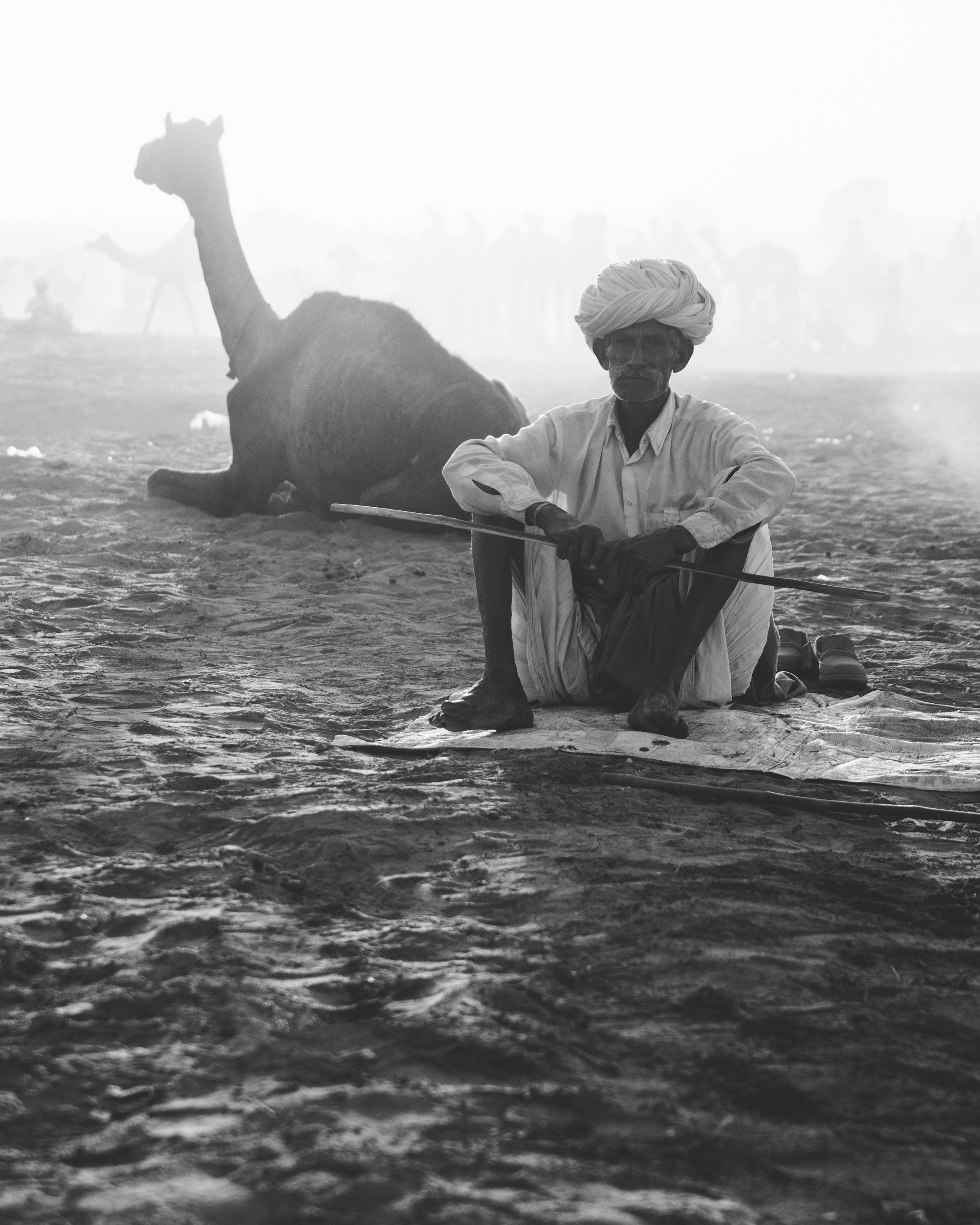

2019 was a much needed recovery year for British Columbia’s Wildfire Service but that didn’t mean that Canadian Wildfire Firefighters got to take the summer off. While BC recovered with cooler temperatures Northern Alberta experienced an unprecedented fire season. Extreme drought conditions in extreme fuel types set the stage for some of the most volatile fire behaviour that the Rangers had ever encountered. Alberta’s wildfire fighting capacity was stretched to the limits with a total of 803,000 hectares of forest burnt between March 1st and June 24th. Resources from all over Canada and the US were being poured into the firefighting effort with the majority, including ourselves, heading to the High Level fire. With a grande total of 350,134 hectares burnt and roughly 4750 people evacuated this fire was the provinces top priority wildfire. The Rangers spent two back-to-back 19 day deployments in High Level fighting the odds as temperatures sat in the high 20s low 30s coupled with low humidity and frequent wind events that gusted up to 75 km/hr. With drought conditions so extreme that old prediction models where being rendered irrelevant operations was having a hard time coming up with a viable game plan that didn’t compromise their crews safety and we watched as an 80,000 hectare fire continued to relentlessly double in size under these unfavourable conditions. We were constantly beat back and tactical withdrawals from the line were a regular occurrence. When fire behaviour is that intense, crews work on steering the fire in certain directions and away from valuables. Indirect tactics such as large scale burn offs were highly effective and created a buffer zone around the town of High Level. By the end of June the weather finally started to turn and it looked like Alberta would be in the rear view mirror for the rest of the summer.

The rest of the season was spent in the Coastal mountains of the NorthWest were we faced steep terrain and challenging danger trees. Coastal trees tend to be much bigger and in this particular stand the Hemlocks were exceptionally dangerous. Common characteristics were rotten holes half way up the stem that would catch on fire and burn the tree from the inside out almost undetected. By the time the tree was ready to fail it was too late to anything about it and a 150 foot high tree with a diameter of 4 feet would snap in half and slam into the ground with a crash like thunder. Every day you'd hear the cannon-like booms and hope that the next one wasn’t going to be too close. However the Danger Tree Fallers were exceptional at getting to the trees that posed a threat to our ground crews and there was almost no close calls. I’m sure the fallers would beg to differ.

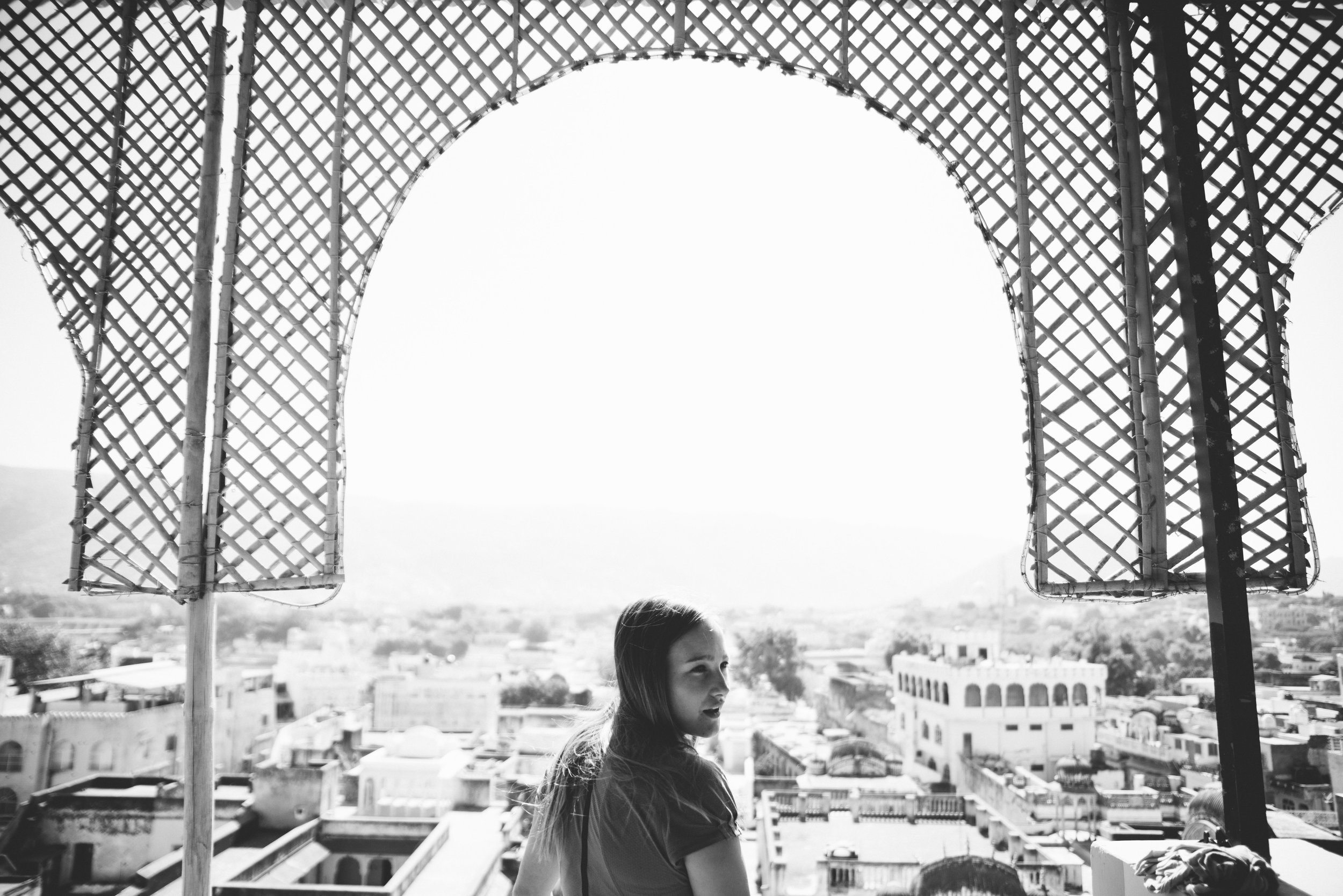

As the season winds down and comes to an end our days are filled with Fuel Management Projects, training and, as always, speculation. It’s hard to say wether or not the upcoming fire seasons will reflect what has become the ‘new normal’. It seems that if British Columbia isn’t having a record breaking fire season you merely have to look to one of our fellow Provinces to see that they’re engaged in a dog fight similar to that which we experienced over the last couple years. Wildfire is unpredictable and you can’t be sure whats going to happen until it’s right on your doorstep. The BC Wildfire Service is taking more action than ever to ensure that preventative measures are put in place to lessen the effects of Wildfire. The trend of bad wildfire seasons definitely seems to be on the rise but so does our ability to adapt, handle and understand these natural phenomena. I hope that these images provide a little insight into what that looks like and that you come away with better understanding of what it means to be a Wildfire Fighter.